Fires That Changed Our World

Learning to make and control fire was one of the defining achievements in the evolution of mankind. Having fire meant that we could keep warm in winter, broaden our diets, ward off predators and forge better tools and weapons. As a result, we were able to stop hunting and gathering and instead build more permanent homes and learn to farm animals and grow crops.

In short, without fire, mankind would not have managed to become the dominant species on our planet.

But it’s not just fire in general that has had an effect on us. Individual fires in our history also stand out as being significant in one way or another, whether it’s because they were a particularly notable historic event, like the Great Fire of London, or because they marked a major change in the way we managed fire safety in specific areas of our lives.

The following are just some of the fires that have had a significant impact both on our lives here in the UK and also in the wider world.

The Burning of the Great Library of Alexandria

Alexandria’s Great Library held thousands and thousands of scrolls that comprised much of the existing wisdom and knowledge, not only of that era but also of the preceding millennia. Although the library itself wasn’t totally destroyed by one individual conflagration, many of its most valuable possessions were destroyed in one night in 48 BCE, during the Roman civil war between Julius Caesar and Pompey the Great.

Although we can’t be certain how it started, the most likely culprit would seem to be Julius Caesar. Besieged at Alexandria, he (or, probably more accurately, troops under his command) allegedly set fire to his enemy’s ships in port, but the fire spread to warehouses onshore.

According to historian Cassius Dio “books, said to be great in number and of the finest, were burned”. That simple statement hides a terrible loss. It’s impossible to know exactly what was lost that night, but it’s no exaggeration to say that it would have set back the course of civilisation by many years.

The Great Fire of London

Although much of London was destroyed in the fire that began on 2 September 1666 at a baker’s shop in Pudding Lane, surprisingly few lives were lost. Estimates suggest that it might have been fewer than ten.

The long-term effects were more significant. Although much of the capital needed to be rebuilt, there was surprisingly little alteration to its overall shape or layout. A shortage of housing meant that parts of the city became even more crowded and as a result even more squalid. That in turn led to many of the capital’s wealthier citizens retreating to the suburbs.

One of the good things to come out of the fire was the development of dedicated firefighting units, although it has to be pointed out that the driving force was financial rather than any particular interest in protecting the lives and property of the capital’s citizens. They came about because some enterprising businessmen spotted an opportunity for fire-related insurance and hired firefighters to prevent too much damage in the event of a fire, and thus keep payouts to a minimum.

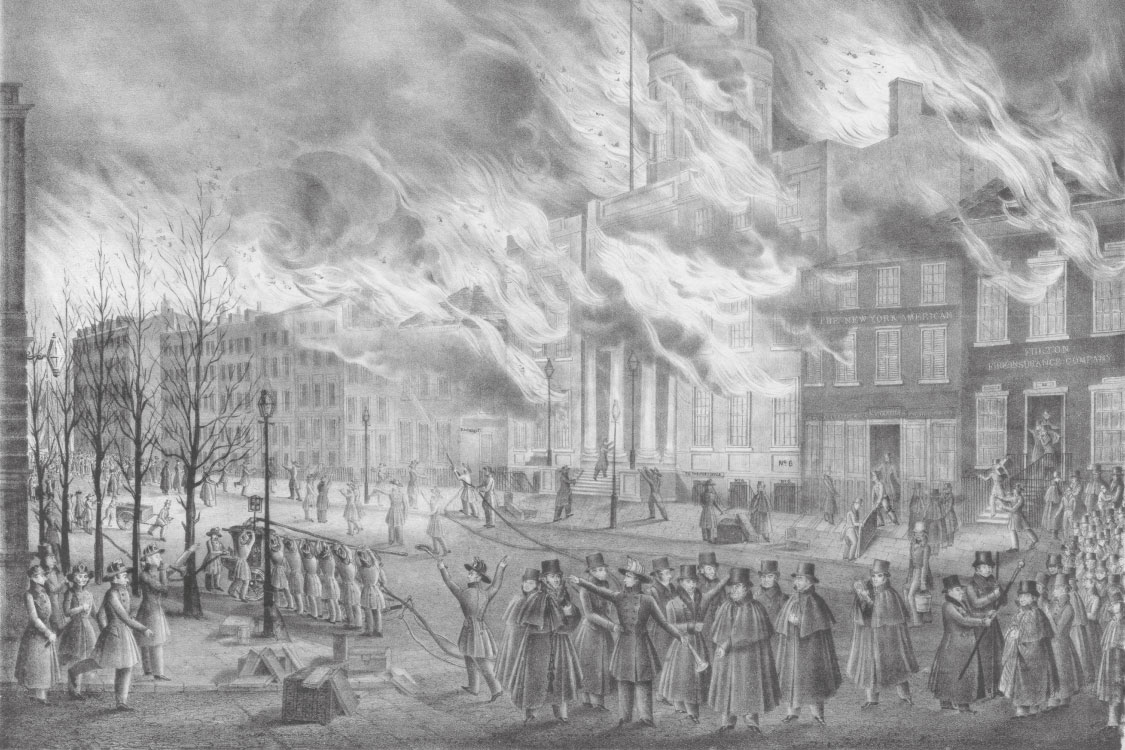

The Great Fire of New York

Today, New York is one of the world’s great cities. In 1776, it occupied only half of the island of Manhattan and had a population of about 25,000 (Philadelphia was the largest city in the country at the time, with about 40,000 residents). How the fire that took place there on the night of 21 September that year began is still a mystery. The American War for Independence was still in full flow, and only a few days earlier the British had invaded and captured New York.

Some say the fire was lit by Patriots to prevent the British benefitting from their newly-won prize; others suggest that it was in fact the British who started it to ease their plunder of the city. However, most accept that it was probably an accident and that – as with the Great Fire of London – it was a combination of dry weather, strong winds and tightly packed wooden buildings that enabled it to cause such devastation. About a quarter of the city’s buildings are believed to have been destroyed.

Despite the extent of the damage, it didn’t take long for the city to recover and grow – if anything, it literally provided the spark for New York to become the most important city in the country. It became the first capital city of the USA shortly after the war and surpassed Philadelphia in terms of population in 1790 (although the capital was moved to Philadelphia that same year). Over the course of the 19th century, the population rocketed from some 60,000 to almost 3.5 million, also becoming one of the world’s most cosmopolitan cities in the process.

The Reichstag Fire

Despite failing to get a majority in the elections of November 1932, Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany on 30 January 1933. Four weeks later, on 27 February, an arson attack by a Dutch man named Marinus van der Lubbe led to the German parliament building – the Reichstag – burning down. Hitler used the event to convince President Paul von Hindenburg that the fire was part of a coordinated Communist attack on the German state and was granted extraordinary powers.

These included the suspension of a wide range of basic civil liberties and rights, including freedom of expression, freedom of the press and the right of free association and public assembly. Hitler used those powers to crack down on his opponents, allowing him to cement his position and win an even larger share of the vote in another election held in 1933. It’s no stretch of the imagination to say that without the Reichstag fire, the Nazis may never have been able to seize total power in Germany.

At his trial, van der Lubbe denied he was a Communist, claiming he acted on his own. Nevertheless, he was found guilty and executed. The case has not been allowed to lie, however, with his conviction being overturned several times – once he was posthumously (and therefore somewhat pointlessly) sentenced to eight years in prison rather than death, while on another occasion he was found not guilty by reason of insanity. He was eventually pardoned in 2008.

Bradford City Stadium Fire

When Bradford City and Lincoln City kicked off a Division Three match at Bradford’s Valley Parade stadium on 11 May 1985, not many would have expected the game to have had any kind of lasting impact. After all, it was the last game of the season, and Bradford had already won the league title. The trophy was presented before the game, with the celebratory atmosphere attracting a bumper crowd of over 11,000, about twice their average attendance for the season.

Unfortunately, the ground was well past its best – in fact, the main stand had remained substantially unchanged since it had been built in 1911. Made of wood, and with gaps between seats where litter could – and did – fall, it was a fire waiting to happen.

That fateful afternoon, a lit cigarette was dropped onto the litter below. Within four minutes, the entire stand was alight. Some spectators were trapped in their seats, while others trying to escape out the back could not get through the locked barriers designed to keep others out. In all, 56 people died and 256 were injured.

That day’s events resulted in a swathe of new legislation designed to improve safety at sports grounds and, along with the Hillsborough disaster four years later, marked a major turning point in the match-day experience for football fans across the country.

The King’s Cross Fire

Smoking on London’s Underground trains was officially banned in July 1984, with smoking in all Underground stations being banned in February 1985. However, with there never having previously been a fatal fire on the Underground, staff had become complacent, with impatient smokers going unchallenged as they lit up on their way up the long wooden escalators on their way out. Staff had also had little – if any – training in the best way to deal with a fire or evacuate a station in the event of one starting.

At about 7.30pm on 18 November 1987, one of those smokers dropped a match onto the Piccadilly Line escalator at King’s Cross St Pancras station. Once the fire had taken hold and it was realised that expert help was required, summoning that assistance took far longer than it should have, because someone had to go to the surface to call for the fire brigade. As the fire grew, some twenty layers of old paint on the tunnel’s ceiling absorbed the heat until, eventually, a flashover caused a jet of flames to shoot up the escalator shaft. The ticket hall was filled with thick black smoke and intense heat, killing and seriously injuring many of the people there.

In all, 31 people died and another 100 were injured – one dreads to think what the toll might have been if the fire had taken place during rush hour.

Following the fire and a subsequent inquiry, the Fire Precautions (Sub-surface Railway Stations) Regulations 1989 were introduced to deal with most of the issues that had caused and intensified the fire, or which had hindered its control. The last wooden escalator on the London Underground, at Greenford station on the Central Line, was eventually decommissioned in 2014.

Grenfell Tower

We don’t yet know what lessons will be learned or what substantial changes will come about as a result of the terrible events of 14 June 2017. At the time of writing, squabbles still persist as to who should pay for the removal of the cladding on high-rise buildings that has been identified as one of the key reasons the fire spread so fast up the tower block, trapping the residents within.

There was also criticism of the fire service’s ‘stay put’ advice whereby residents are told to stay in their flats unless they are directly affected by the fire. This is a standard fire safety procedure in high-rise buildings with single stairways in many countries – but the rationale does depend on whether adequate standards have been met in the construction and maintenance of the building in question.

The fire itself started as a result of a malfunctioning fridge freezer on the fourth floor of the 24-storey building. 72 people died, making it the worst residential fire in the UK since World War II.

An inquiry into the fire was launched in two phases: the first covered the events of the night in question and was published in October 2019; the second, looking at the wider situation, is still ongoing.

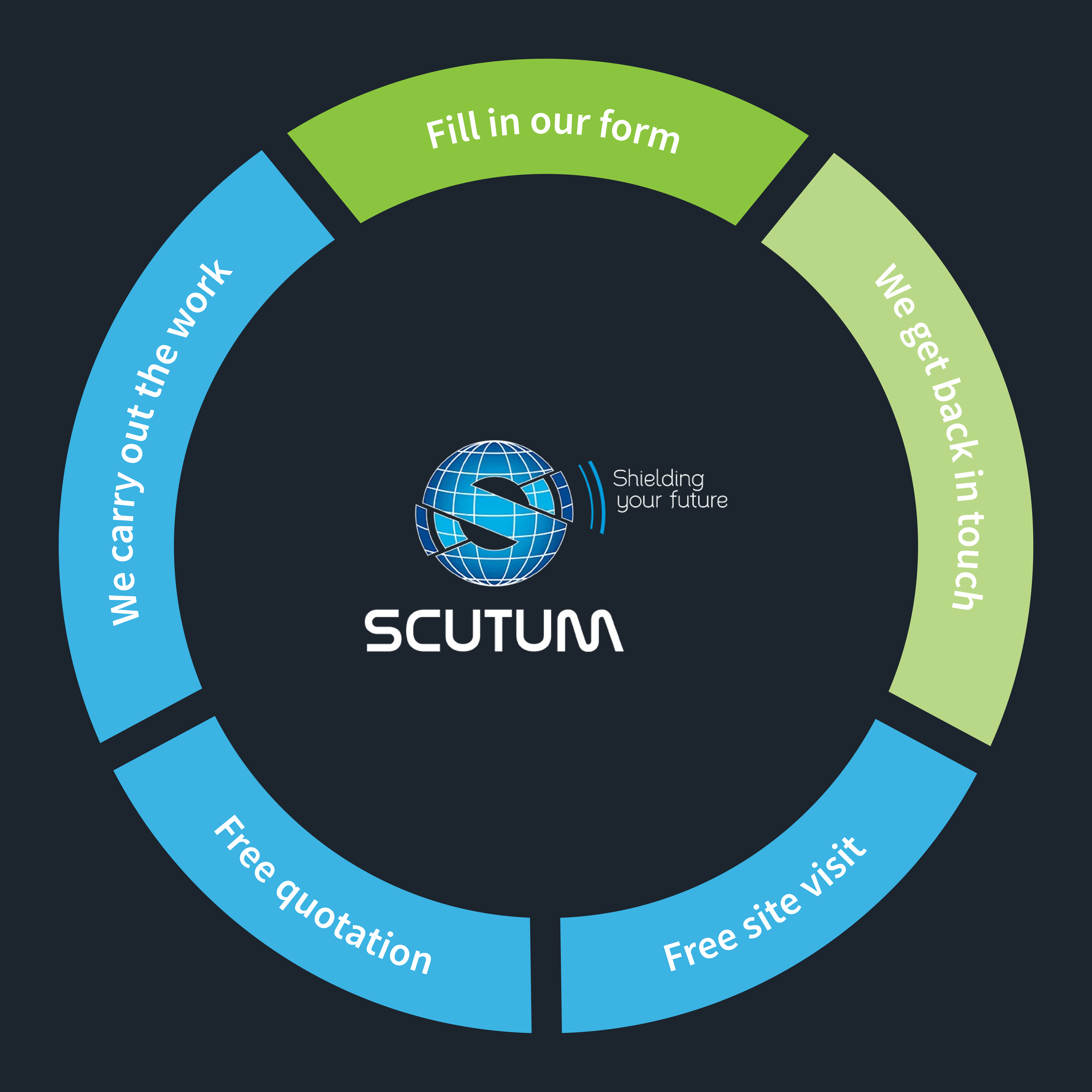

With each event, we learn more about what can be done better in terms of preventing, detecting and controlling fire. Here at Scutum London, we’re recognised as being one of the leading fire safety companies in the London and Surrey areas.

We provide expert fire risk assessments, together with reliable fire alarm systems, appropriate fire extinguishers and a full range of other fire safety measures. Contact us now for more information or to book a fire risk assessment for your business premises.

Request a Callback

Just fill in your details below and we'll get back to you as soon as we can!

About Scutum London

Scutum London is a leading expert in fire safety and security solutions for businesses and organisations located across South East England, including London and Surrey.

From fire alarms, fire extinguishers and fire risk assessments to access control, CCTV and intruder alarm systems – and a lot more besides – we offer a comprehensive range of products and services designed to keep you, your business and your staff and visitors safe.

With decades of industry experience to call on, we’re proud to hold accreditations from leading trade associations and bodies such as British Approvals for Fire Equipment (BAFE), the British Fire Consortium, the Fire Industry Association (FIA) and Security Systems and Alarms Inspection Board (SSAIB).

If you’d like to find out more about Scutum London, get in touch with our friendly team or explore our products and services on our site.